If you’ve ever seen adult jumping worms, there’s no mistaking them. Found near the surface of soil and larger than your average worm, jumping worms don’t actually jump, but they thrash and wriggle about so violently it can seem like they are jumping. They have a distinctive raised band near their heads and leave behind castings that look like Grape Nuts cereal.

Originally from Asia, there are a few types of jumping worms (they are among about 120 worm species that are considered invasive out of 7,000 total types of worms). Gardeners dread finding jumping worms in their beds and fear that they could ruin their soil. We spoke to two scientists who are studying jumping worms, Dr. Annise Dobson, director of research programs and associate research scientist at Yale School of the Environment, and Dr. Maryam Nouri-Aiin, a postdoctoral researcher at University of Vermont’s Agriculture, Landscape, and Environment School.

Featured photograph of mulch (beloved by jumping worms), by Justine Hand, from Pollinator Gardens: 8 Easy Steps to Design a Landscape with Native Plants.

Are jumping worms a new phenomenon?

While the worms may seem like new invaders, Dr. Dobson explains that jumping worms have been in the U.S. since at least the 1940s. “It seems like there have probably been hundreds of separate invasions. So it’s a little bit different than, say, beech leaf disease that started out in one place and it’s got this very clear path.”

How do they ruin soil?

Jumping worms become destructive when their populations reach high densities, especially in forests, but also in gardens. “They are really voracious eaters. They devour the soil, leaves, and organic matter in a really short amount of time,” explains Dobson. Then the worms deposit castings on the top of the earth, creating a change in the quality of the soil so that it acts almost more like gravel. It erodes more easily and dries out quickly, which makes it hard for things to germinate. These conditions that make it difficult for plants to take root are particularly problematic for forests, especially ones that are already under stress from disease, drought, or deer pressure.

While jumping worms are disrupting the ecosystem in the forest, they are less likely to do so in the garden. Trees and established perennials will not be affected by jumping worms, but annuals or tender seedlings may struggle to take root if they are present.

Is there any way to prevent them from popping up in your garden?

Mulch and wood chips are the most likely way that jumping worms will enter your property. “They tend to really like mulch piles and wood chips,” explains Dobson. If you get mulch or wood chips in the spring when the cocoons are as tiny as a poppy seed, there’s no way to know if they are infested. But, Nouri-Aiin adds, “It’s not the nursery’s fault. At this point it’s basically impossible to avoid them.”

Solarizing mulch or wood chips, though, will kill the jumping worms. Nouri-Aiin ran an experiment to see how long and how hot you need to get compost or mulch to kill different life stages of jumping worms. She found that 104°F (40°C) for two hours was enough, but you have to make sure it’s hot all the way through the material, so she’d recommend three hours to be safe. Additionally, the pile has to be insulated from the soil because the earth could keep the bottom cool, so lay out a layer of cardboard beneath the mulch before covering it with plastic sheeting to solarize.

If you’re bringing in plants from a nursery or plant sale, take a look at the soil when you pop the plant out of its container and make sure that there aren’t any of the distinctive castings in the soil, especially on the top. If you can, opt for bare root plants.

How do you get rid of them if you have them?

Even if jumping worms are driving you crazy, do not resort to applying pesticides to your garden beds. There is no pesticide that is appropriate to use on jumping worms, or any earthworms in general. Some people swear that they if are vigilant about hand-removing jumping worms over multiple years, they can get the population down, but Dobson says this method has not been studied. (Dobson doesn’t bother to remove worms in her yard, but Nouri-Aiin says she does.)

One method that doesn’t work: mustard. Some websites recommend using mustard to deter jumping worms, but Dobson describes this misinformation that came about as a bit of a game of Telephone. “Scientists use ground mustard to evaluate earthworm populations because you can mix it with water and pour it on the soil. This makes them come up to the surface, so you can count them,” she says. But this is done on a 50×50 centimeter quadrant: The amount of mustard that you would have to use to get rid of jumping worms is an impossibly large quantity of mustard.

Wait, so if you have an infestation, you’ll always have an infestation?

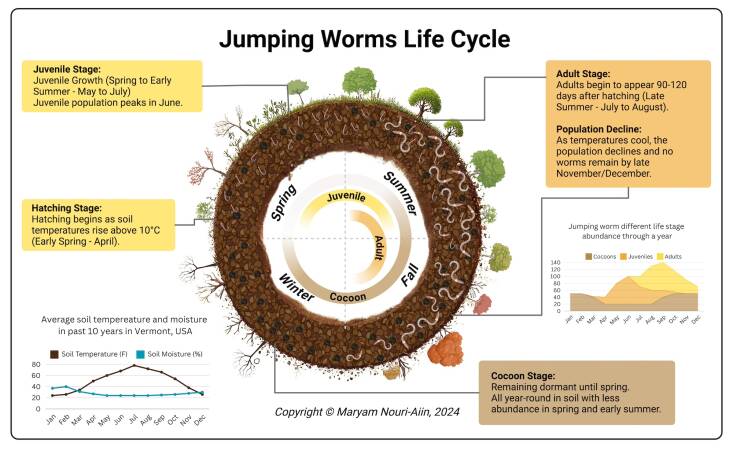

If you end up with an infestation, take heart that jumping worms’ life cycle is only a year long, and Dr. Nouri-Aiin says that a big population one year will not necessarily lead to a similar or larger population the following year. “One year there are tons of them, and then next year you go to the same spot and you expect to see even more because there were too many adults reproducing at the same time, but you won’t find even one.”

What can you do to help stop their spread?

The worms don’t move far on their own, but many gardeners who live at a woodland edge will toss their clippings and other yard waste into the forest, which can unwittingly help worms enter forest ecosystems. You should never do this if you have jumping worms (or really any time, just to be safe). “A little sanitation could help a lot,” says Nouri-Aiin. And this goes without saying, don’t share infested plants with others.

If your yard is deeply infested with jumping worms, you can help scientists with their research by reporting it. Dobson says the easiest way to do so is using iNaturalist’s Seek app or the site imapinvasives. Nouri-Aiin also has a research project going this summer in Vermont that community scientists can help with (sign up here).

See also:

- Search & Destroy: Goutweed, the Invasive Ground Cover of Your Nightmares

- Search & Destroy: Scarlet Lily Beetles

- Search & Destroy: Lesser Celandine

Have a Question or Comment About This Post?

Join the conversation (1)