The rewilding project at Knepp, a farming estate in Sussex, England, has been well-documented, first with c0-owner Isabella Tree’s best-selling eco-memoir, Wilding—and now with her new book, The Book of Wilding: A Practical Guide to Rewilding Big and Small. Written with her husband Charlie Burrell, whose family bequeathed him an infertile and unprofitable farm 11 years ago, it is a rewilding manual for serious enquirers, a preparation-results-conclusion guide to achieving a phenomenal surge in biodiversity on anyone’s land.

Rewilding has been interpreted as permission to let go, to let weeds trip people up as they navigate city streets, or to sit back and watch the most vigorous plants take over our once-tended green spaces. “Time to End the Rewilding Menace,” Julie Burchill argued in the Spectator a few weeks ago, while the British press created a storm over comments from gardeners Monty Don and Alan Titchmarsh (who respectively called it “puritanical nonsense” and “an ill-considered trend”). Anyone with an interest in maintaining the status quo is against rewilding, we are led to believe.

There is a distinction between wilding and rewilding, arguably. Rewilding a large tract of land involves healing a landscape and reintroducing missing fauna and mega-fauna (or at least mimicking their activity in the interim) as a step towards restoring ecological function. Wilding a garden on the other hand is beautifully attainable for all; a wilded flower pot, tree pit, stoop, or balcony may sound a bit silly, but it just comes down to being guided by nature when planting, rather than relying on received ideas.

Photography by Jim Powell, except where noted.

The subject of wilding and rewilding is complicated, as reflected in the book’s size (560 pages). For speed readers, it is absurdly easy to mock. In the chapter “Becoming the Herbivore,” we are directed to replicate the a “pig nest” and a “stallion latrine” (introducing dung to encourage nettles). For anyone coming to grips with just mowing their lawns less frequently, it can be disquieting when a gardener says, “You are the bison.” What they are trying to tell you is that in the absence of keystone species—roaming herbivores—it is up to us to create optimal conditions for biodiversity with our own periodic disturbance: roughing up terrain and making inviting pockets for habitat, spreading seeds as an animal would in their hooves and fur, interrupting the impulse of trees to grow up into a closed canopy forest. Anybody with a serious amount of land can leave this to wild ponies, elk, and rare breed pigs.

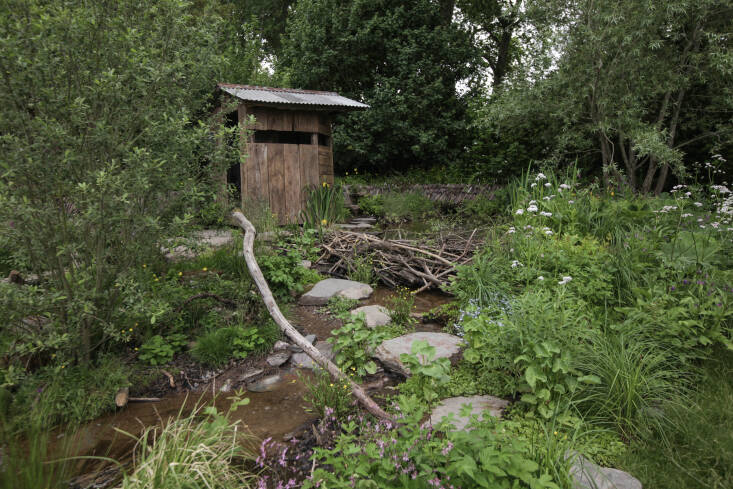

Burrell is a board member of Rewilding Britain, the charity (supported by Project Giving Back) that put on a show-stealing garden at Chelsea last year, designed by Lulu Urquhart and Adam Hunt. Not everyone would agree with the authors’ description of the Royal Horticulture Society’s flagship show as “that bastion of horticultural convention and neat-freakery,” and it seems a little churlish given that the garden won best-in-show. It is not inherently green to build an intricate edifice for one week, only to take it down again, but the show has always sparked an almost out-of-proportion national dialogue. It’s good to talk.

For many visitors to the Chelsea Flower Show, gardening is about shopping, but it would be far more beneficial to a garden that is on its way to being wilded to not buy things. Step away from the garden center; instead, swap seeds and plants, and rather than buying birdhouses shaped like beach huts, grow shrubs for habitat and shelter. This should be music to anyone’s ears: “Spending less is a defining characteristic of rewilding and nature-friendly gardening.”

One criticism of the rewilding movement (in the US at least) is its prioritizing of fauna restoration as a general picture, over the specific role of flora. In other words, the movement is less puritanical than ecological gardeners would like. The argument goes that ornamental plants mixed with natives are fine, since the former see plenty of general wildlife activity. Less examined is the fact (taken far more seriously in the US) that specialist feeders and breeders can only use hyper-local, native plants. Purists will also take issue with the idea of swapping out soil conditions in order to meet personal or aesthetic needs. In the refurbished walled garden at Knepp, fertile topsoil was exchanged for tons of crushed concrete and brick, to implement a design by Tom Stuart-Smith, and this is happening all over.

Sales of native plants in the US are at an all-time high, while the conversation around gardens as habitat is at last becoming more mainstream. It is tempting to be distracted by the idea of wolves roaming the streets (predators being key to the trophic pyramid). But ten years ago all these ideas were very “niche” and we were ignorant of our own ignorance. Let’s keep arguing.

Knepp is open for stays and safaris, since its success needs to be seen to be believed. “Seeing how nature can bounce back in such profusion and with such astonishing speed, especially on land as unpromising as ours, is both profoundly reassuring and galvanizing.”

The Book of Wilding: A Practical Guide to Rewilding Big and Small by Isabella Tree and Charlie Burrell, was published last week by Bloomsbury.

See also:

- Required Reading: ‘The Farm Table’ by Instagram Sensation Julius Roberts

- Ask the Expert: Regenerative Organic Gardener Emily Murphy on How to Rewild Your Landscape

- What Will Gardens of the Future Look Like? A Report from the Garden Futures Summit

Have a Question or Comment About This Post?

Join the conversation (0)