A new patio project can be daunting. If you’re thinking of adding a patio to your backyard or garden, you probably have a few questions. To get some answers, we talked to landscape architect Bay Area–based Pete Pedersen, whose company, Pedersen Associates, has been based in Marin County since 1983 (and is a member of the Gardenista Architect and Designer Directory. Pete’s had plenty of experience: He and his design team take on from 40 to 50 outdoor projects per year, most of them residential.

Here is everything you need to know about patios.

Patio vs. Terrace: Is there a difference?

“People tend to use the two terms interchangeably,” says Pedersen. “You might say that a terrace is slightly elevated, but for most people they’re the same thing.” Whatever name you give it, he says, “it’s basically just a hard surface where you can put furniture without poking holes in the lawn and falling backwards.”

Where is the best place to put a patio?

Obviously, if your lot is small there’s not much to think about. But if you have space to play around with, you’ll need careful consideration. A professional designer can help you find the best location for your patio, minimizing costs by selecting the flattest area, and maximizing the view (if you have one).

For ultimate convenience, your patio will be right next to your house in an area that’s as private as possible. “Thoughtful siting will increase the use,” says Pedersen. “Let’s face it, people can be lazy. If you have to go down two flights of stairs to have your coffee, you’re not going to do it.”

On the other hand, there’s something to be said for an outdoor room that’s a destination. But, says Pedersen, you need a good enough reason to go there—such as a fire pit: “Like moths to a flame, people will just come to it.” And how you access the spot offers a design opportunity—“You can do fun things with geometry and circulation, with the paths that get people there.”

Do I need permits to build a patio?

One reason you may need a permit is excavation. “If you’re going to be moving a lot of soil around, your town or municipality will generally want to know about it,” says Pete. And second, if you’re pouring concrete, local authorities will want to inspect the site prior to placement.

The Clean Water Act imposes other regulations. “If your patio is a hard surface, and large, you need to deal with the stormwater draining off it,” Petersen says. The patio must be sloped away from house, and if there’s a drain, you may have to treat the water that comes out the other end, perhaps sending it through filtration soils before allowing it back into the environment.

Pedersen says that a sediment and erosion control plan is also required for most permitted projects in the Bay Area, and most likely in other areas across the country. If you’re installing a drainpipe, for example, you need to consider how water gushing out after a rainstorm will affect the surrounding landscape—especially if you’re on a slope. One way Pedersen solves this problem is by installing a perforated dispersal pipe to spread the water out.

Do I need a patio railing?

Building codes allow residences to have up to a 30-inch change of elevation without the need for a guardrail. (And you should have at least three feet of flat ground below that 30 inches.) “I try to keep it less than that,” says Pedersen. “If you have 24 inches, it can function as informal seating.” Sometimes, after considering how the area will be used, they’ll add a guardrail even when there’s not much change in elevation—“You don’t want a kid on a Big Wheel doing an Evel Knievel into the shrubs,” he says.

What are the best patio paver materials?

Pedersen believes that the choice of materials should be driven by the architecture of the building and the patio’s intended use. “When the patio design takes its cues from the architecture, it gives you a more seamless look, especially when the scale is intimate,” he says. “With larger lots you have more opportunity to do different things, but I still like to tie my design to the framework of how the whole site is being developed, making it a team effort with the architect, and making it period-appropriate.”

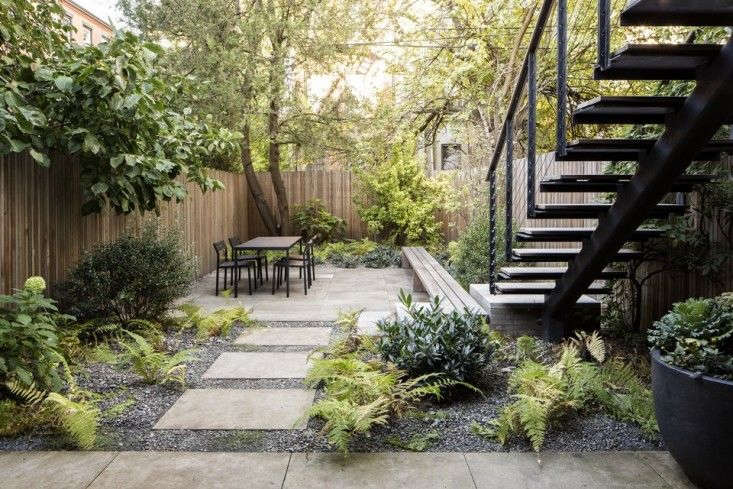

Pedersen doesn’t have a single material he prefers: “I look at all the conditions and pick materials that echo throughout the property.” For a formal patio intended for entertaining, he likes to put in a hard surface that allows guests to wear high heels. “You can modulate that by adding bands or gravel strips running through it—as a design element that also help the permeability.”

Brick wouldn’t be his first choice for a patio, unless there’s brick on the building. “Because the modules are small, you have to handle a lot of pieces, and you’re paying a mason to do this work. Larger pavers go down faster.” Also, bricks need to be laid on a compacted base or set in mortar. “But you can do fun patterns and mosaic designs with them.”

Concrete matches well with contemporary minimalist architecture. “When we’re laying concrete slab, we use integral color to make the concrete look like natural stone, or color hardener concrete for more intense shades,” says Pedersen. And while there used to be few options for concrete pavers, “now there’s a huge array, including large-scale random-patterned pavers that are really attractive.” Pedersen recommends Hanover, Calstone, and Belgard.

His company designs a lot of patios in crushed rock and gravel, generally starting with compacted road base material and then top-dressing it with three-quarters of an inch of crushed rock. “That gives you a nice uniform look that’s easy to maintain and easy to walk on,” he says. (Not so much, however, for those women in heels.)

An all-gravel patio tends to give a little too much—“You feel like you’re walking on the beach,” says Pedersen. A better bet is decomposed granite (DG), which he describes as being like a baseball infield. “Binders will hold the surface tightly for foot traffic, and it comes in different colors. You can’t use DG on a slope, but it’s an inexpensive material for a larger level surface, if you want to, say, throw up a harvest table for entertaining.” And, he adds, the cost is much lower than other options.

What are the best guardrail materials?

As for the guardrail material, Petersen says this choice should also be driven by the architecture. “We’ll do glass for a house that’s sleek and contemporary, or maybe a cable rail with stainless steel posts,” he says. “For a more traditional house we might do wood pickets and have some fun with patterns.”

How long will a patio last?

Patio durability depends on the materials used. Most stone has a long life expectancy, though some stone weathers faster than others; Pedersen avoids slate and Arizona sandstone for that reason.

“With gravel, there’s always a level of maintenance,” says Pedersen. “You can lay weed blankets, but that’s not a long-term solution.” DG also needs freshening up now and again. “But these surfaces can last as long as you want to maintain them.”

As for concrete, Pedersen repeats an old contractor’s joke: There are two kinds— concrete that’s cracked, and concrete that will crack. “Cutting it into pieces can minimize cracking and help it last longer,” he says. But any concrete surface will show more sand after 10 to 15 years of being exposed to the elements.

Do you need a pro to design a patio?

If you know the shape and size because you have limited space, says Pedersen, you could probably lay it out yourself using string and stakes. But he feels it’s better to bring in a professional—“from day one!” he quips.

Hiring a pro will help you get the most out of your space. After all, you’ll be spending some money, and you want to be certain you’ve chosen the right spot for its intended use, you’re dealing with the drainage properly, you’re using the right materials, and you’re considering life span issues. Most important: a designer will be able to estimate the cost.

Whoever you get to design your patio, it should be someone who just does design. “There are lots of contractors who’ll design the project and also build it,” says Pedersen. “But to my mind, that’s like the fox watching the henhouse, in terms of your budget.” He also notes that design/build contractors tend to design for the things they do—if they have a good carpenter, for example, you’re sure to get a trellis and a fence in the design. “You want a designer who has no need to keep people busy.”

Patios: DIY vs. Hiring a Contractor

Is DIY a possibility? It depends on the scale of your patio project, what the site requires, and of course your personal skills. A small patio on a flat area can be fairly straightforward; online DIY videos will tell you how to do it.

But in an area with a lot of topography, it can be a challenge to find usable space. “If it’s going to be a raised patio,” says Petersen, “you’ll need perimeter footing—perhaps steel and concrete—and a way to address drainage issues.”

And if permits are required, you’ll need to generate a site plan, showing spot elevations so you know where the runoff is going. Building steps means more regulations to comply with.

What is the average cost of a patio?

Pedersen cites a range of prices (that include materials and labor) for building a patio in Northern California. Costs can be lower in other parts of the country, but possibly higher in more urban areas:

- A concrete patio will cost from $10 to $15 per square foot.

- Decomposed granite is at the low end, $7 to $10 per square foot.

- Sand-set brick runs $20 to $25 per square foot.

- Sand-set pavers cost $20 to $25, depending on the stone.

- Putting stone or pavers on top of concrete can run from $35 to $40.

- Using cut stone is the most expensive option—sometimes the stone alone is $20 per square foot, so the cost with labor can be as much as $50 per square foot. Adding intricate patterns, inlays, or bronze edging will push the price higher.

How can I cut the costs of a new patio?

Pedersen advises keeping the materials and design simple. “Rectangles will help control the budget,” he says. “Doing soft radiuses and turns requires a lot of cutting, and that increases the labor. Keep the geometry simple and don’t fight your module—the reason houses are rectilinear is because wood is rectilinear.”

His second tip: Don’t dig too deep. “When you begin to move a lot of soil, costs go up. Site work and excavation are one of the most expensive parts of any project.”

N.B.: Planning a patio project? For design tips, layouts, and the best materials, see Decks & Patios 101: A Design Guide. For more projects, see our Hardscape 101 design guides to Fences & Gates 101 and Pavers 101. And browse our posts on materials:

Have a Question or Comment About This Post?

Join the conversation (3)