I love the New York Botanical Garden: the frothy pink cherry blossoms and vibrant azaleas in spring, the lush native plant garden dotted with birds, the majestic old trees growing throughout the landscape’s 250 acres. I’ve been visiting since I was a child, and always come away with a new fascination. One of my recent discoveries is the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium, an under-the-radar treasure trove established around the time the garden was created in 1891. I talked with Dr. Emily Sessa, the herbarium’s director, to learn more about it.

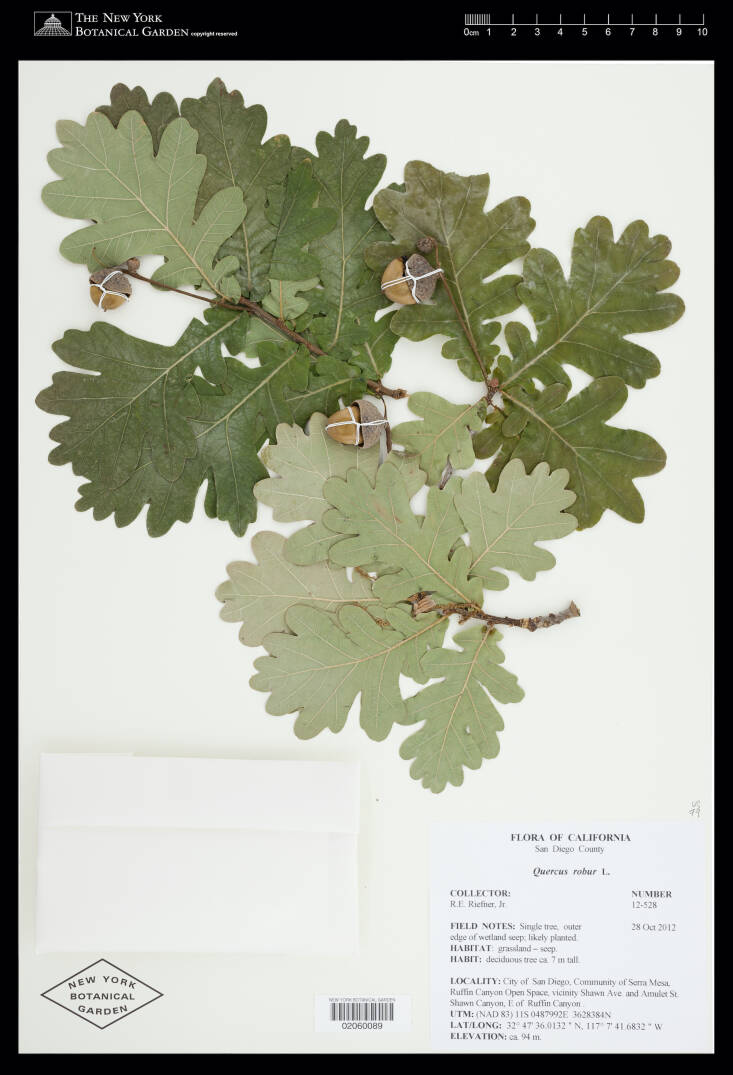

“An herbarium is a museum of plants that documents biodiversity,” says Sessa. The collection, one of the largest in the world, contains nearly eight million specimens of pressed and dried flora—flowering plants, conifers, ferns, mosses, algae, and liverworts (including a selection collected by Charles Darwin in the Galapagos), as well as fungi and lichens—from around the globe, dating back to the 1600s. “It’s like a time machine. You can walk into the herbarium, open a cabinet, and not know whether you’re going to be in 1950 or 1750 and whether you’re going to be in London, Rio Janeiro, or Accra,” Sessa says. “It’s an amazing way to explore time and space via plants.”

Each specimen captures a moment in time. “When scientists are in the field, we always travel with a plant press, corrugated cardboard, and newspaper,” Sessa says about the collecting process. “The technology hasn’t really changed much over the years.” When pressing, a scientist is careful to show both sides of a leaf, or if it’s a flowering plant, display both the fruit and the flower. After collecting and meticulously labeling each item, they bring the press, packed full of plants, to an herbarium where the specimen will be dried (“humidity and dampness are the biggest enemy,” says Sessa). Then it’s mounted on acid-free paper.

From there, the documents help scientists around the world research everything from DNA sequencing to plant conservation. “We can’t make decisions about which species to conserve or which areas to protect if we don’t know what’s there,” says Sessa. It can help track invasives by showing how a species spreads over time. For instance, the New York Botanical Garden (NYBG) has the first documented specimen in North America of purple loosestrife, the beautiful but aggressive purple flower that has been invading our wetlands. “We can map how it has spread decade by decade,” she says. Scientists also can demonstrate the effects of climate change on plants by monitoring bloom times of a specific species found in the herbarium, noting, for example, how 30 years ago certain plants that flowered in June are now blooming in May. And it can be used to help find creative solutions for climate problems. One scientist recently came to sample plants to research fire resilience. “The herbarium can be used for all kinds of fascinating applications,” says Sessa.

A great way to get acquainted with the herbarium is though The Hand Lens, the blog written by Sessa and her team. It highlights notable pieces from the collection, with entries such as Plantways of the Lenape People and NYBG 2021 New Species Review. Visitors to the NYBG can also make an appointment to tour the Herbarium with a staff member. But you can always access the digital C. V. Starr Virtual Herbarium any time you want to explore for yourself. Here is a selection of specimens from the collection, with descriptions from the NYBG.

Photography courtesy of the C. V. Starr Virtual Herbarium of The New York Botanical Garden.

For more on NYBG, see:

- Garden Visit: Lessons from the Impressionists at the New York Botanical Garden

- Required Reading: The New York Botanical Garden

Have a Question or Comment About This Post?

Join the conversation (0)