When the perfume of linden trees drifts across New York neighborhoods, I know that it is serviceberry season. Roses have been flowering for weeks, Japanese honeysuckle has erupted. It’s June. Red and purple when ripe, with a faint bloom on their skins, serviceberries hang in clusters from graceful trees. Locally, they are often planted in public landscapes for their spring blossoms, blazing autumn foliage, and graceful resilience in the face of urban adversity. In good fruit-bearing years their branches may bend low, making it easy to reach up and collect the sweet fruit, although often it drops to the sidewalk, untouched. Despite their native status, outstanding flavor, and ability to keep well (refrigerated), serviceberries are rarely seen at market. This is curious, because they are uniquely delicious.

Photography by Marie Viljoen.

Serviceberry is one of a slew of common names for the different species, hybrids, varieties, and cultivars of Amelanchier trees and shrubs. Some common names are associated with a particular species, but mostly they are used interchangeably. So A. arborea, which has dozens of nursery-trade cultivars, is also known as downy serviceberry, juneberry, shadbush, servicetree and sarvis-tree. But it’s hard—even for botanists—to sort out Amelanchier taxonomy, and what you buy at a nursery might not match what the label says. The trees and shrubs tend to hybridize easily, too, making precise identification tricky. They may be multi-stemmed or single-stemmed, they may be tall, or shrubby. What does matter, is how they taste.

Early summer is the time to start sampling.

Most Amelanchier species are native to North America. On the East Coast serviceberries’ pointed, greenly-white buds open to accompany the running of shad (where shad still run), a herring that returns to its birth-rivers to spawn in early spring, giving rise to the names shadblow (blow is old English, from blowan, for blossoms) and shadbush. To Canadians they may be Saskatoon, named from a Cree word for the place where they grew in abundance. Juneberries? It is often the month when they ripen, in Northern summers.

William Clark (of Lewis and Clark) referred to them as “sarvis buries” in his extraordinary travel journal (which inspires equal parts awe and cringe). Native Americans knew serviceberries well. The pounded fruit was an ingredient in regional pemmicans. I have dried the fermented fruit and it is addictively good, tasting like chewy marzipan.

The first serviceberries I tasted grew in a jasmine-scented May garden in the Turkish town of Ayvalik, on the Aegean. Nobody could tell me what they were, only that they were good to eat. I agreed, as I stuffed myself. Back in New York I recognized the same fruit, and suddenly, I saw the trees everywhere. On the Hudson in South Cove Park, in Tear Drop Park, in the then-scrappy parklet* between the Manhattan and Brooklyn Bridges, in Prospect Park, and Central Park. June has become a much-anticipated month.

* Since transformed into the botanically-gleaming Brooklyn Bridge Park, where serviceberries were planted again liberally.

The fruit I ate in Turkey, growing on a sprawling bush, belonged perhaps to the one European species, Amelanchier ovalis (snowy mespilus), which occurs right into central Russia, although the (possibly) American A. lamarckii has naturalized on that continent. And there are Asian serviceberries, too: A. sinica and A. asiatica.

Serviceberries are not actually berries. Like apples and rosehips, their Rosaceae family cousins, they are pomes. Look to the tell-tale coronet at the base of the fruit to recognize a pome. The trees are also share diseases, the most spectacular being cedar apple rust, which produces fascinating fungal growths on affected fruit.

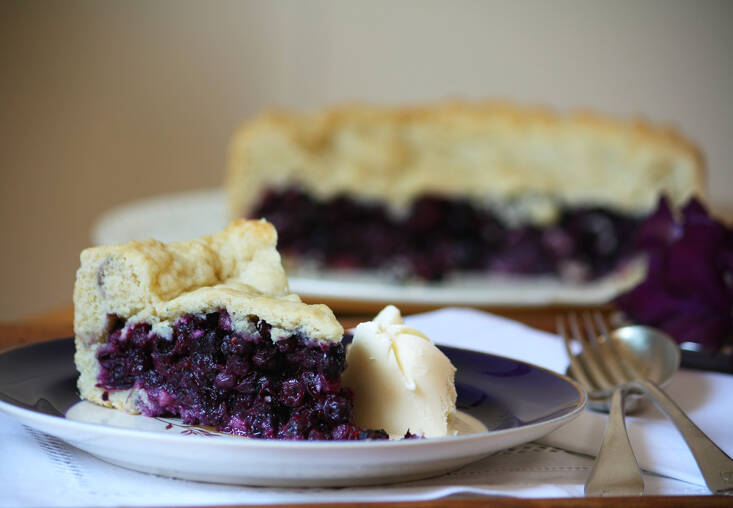

How do serviceberries taste? They are frankly sweet, and, to my palate, like the flavor of cooked apples. But when exposed to heat they are transformed; their small seeds release a frisson of bitter almond, and so Amelanchier pie—which is incredibly good— is redolent of marzipan. The sweetest fruit may be best fresh and raw, like blueberries. But, like blueberries, serviceberries can be used liberally in cakes, muffins and scones, pancakes, sweet breads, syrups, sauces. And ice cream.

I preserve the fruit by extracting a versatile, fermented syrup (made by dumping an equal weight of sugar over them in a large jar, and waiting). That syrup may become a drink, or a pan sauce for duck breasts. The leftover fruit is then dried at room temperature, to be deployed like raisins, except with that marzipan undertone. Dried even further, fermented serviceberries can be ground up into a flavorful sweet powder. The details are in the Serviceberry chapter of my book, Forage, Harvest, Feast – A Wild-Inspired Cuisine.

The sweetest fruit is purple, but red pomes are good to eat, too. Avoid any that have been afflicted by the fascinating, alien-like fungal growths of cedar apple rust. At home the fruit lasts well, covered in the fridge, for weeks, should you have gathered a glut and come to a preparation standstill.

Serviceberry Ice Cream

Makes 1¼ quarts

Cooking serviceberries releases their distinctive marzipan aroma. The smooth tartness of top-quality balsamic vinegar blends lusciously with the fruit.

- 1½ pounds serviceberries, picked from stems

- 8 ounces sugar

- 2 cups half-and-half, cold

- 1 cup whipping cream, cold

- 2 Tablespoons balsamic vinegar

Combine the serviceberries and sugar in a saucepan. Place over medium heat and cook until the juice begins to run, stirring occasionally to prevent sticking. Allow the oozed juices to boil for 1 minute, then turn off the heat. When the mixture has cooled, press it through a food mill (I like the easy-to-use and clean Oxo) to extract the seeds and any sneaky stems. If you do not have a food mill, purée the fruit in a blender and work the mixture through a fine-mesh sieve into a bowl.

You should be left with 1 cup of purée. Chill it thoroughly in the fridge.

When the serviceberry purée is cold, mix it with the cold half-and-half and cold cream in a bowl. Add the balsamic vinegar. Transfer to the frozen bowl of an ice cream maker and churn until thick. Freeze in containers or dive in at once!

See also:

- Wintercresses: Piquant Spring Greens to Forage

- 11 Favorites: Edible Flowers of Spring

- Chickweed: Taste the Stars

Frequently asked questions

What are serviceberries?

Serviceberries, also known as Saskatoon berries, are small fruits that grow on deciduous shrubs or small trees. They resemble blueberries and have a sweet, slightly nutty flavor.

Can serviceberries be foraged?

Yes, serviceberries can be foraged in the wild. They are commonly found in North America, particularly in the northeastern and northwestern regions.

When is the best time to forage serviceberries?

The best time to forage serviceberries is in late spring or early summer, typically between May and July. You can find them when the fruit is ripe and has turned a deep purple color.

Are serviceberries edible?

Yes, serviceberries are edible and safe to consume. They have been a part of indigenous diets for centuries and are rich in antioxidants, vitamins, and fiber.

What are some ways to eat serviceberries?

Serviceberries can be enjoyed in various ways. They can be eaten fresh by themselves as a snack, used in baked goods like pies and muffins, or added to oatmeal, salads, and smoothies.

Do serviceberries have any health benefits?

Yes, serviceberries are nutritious and offer several health benefits. They are high in vitamin C, fiber, and antioxidants, which are beneficial for the immune system and overall well-being.

Are serviceberries similar to blueberries?

Yes, serviceberries are similar to blueberries in appearance and taste. However, serviceberries have a slightly nutty flavor that sets them apart.

Can serviceberries be frozen?

Yes, serviceberries can be frozen for later use. To freeze them, spread the washed and dried berries on a baking sheet in a single layer, then transfer them to a freezer bag or container.

Where else can I find recipes for serviceberries?

Apart from the provided link, you can find serviceberry recipes in cookbooks focused on foraging, wild foods, or general fruit-based recipes. Online recipe sites and forums may also have recipe suggestions.

Have a Question or Comment About This Post?

Join the conversation